Mapping and Databasing Rare Animals

Our data are essential for prioritizing those species and communities in need of protection and for guiding land-use and land-management decisions where these species and communities exist.

The Zoology Program actively monitors approximately 490 rare animals and animal assemblages Rare Animal Status List (PDF, 882 KB). This includes all rare vertebrates and rare species in select invertebrate groups like butterflies and moths, beetles, dragonflies and damselflies, mayflies, crayfish, land snails, and freshwater mussels. Significant animal assemblages include bat hibernacula, anadromous fish, waterfowl and raptor concentration areas, and nesting areas of terns, herons, and gulls. Our program keeps two lists of rare animal species: the Active Inventory List and the Watch List. Species on the Active Inventory List are ones we currently track in our database; for the most part these are the most rare or most imperiled species in the state. Species on the Watch List are those that could become imperiled enough in the future to warrant being actively inventoried or are ones for which we do not have enough data to determine whether they should be actively inventoried.

| Active Inventory List |

Watch List |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mammals | 17 | 11 |

| Birds | 54 | 49 |

| Reptiles | 15 | 9 |

| Amphibians | 6 | 6 |

| Fish | 59 | 50 |

| Freshwater Snails | 15 | 10 |

| Freshwater Mussels | 39 | 5 |

| Other Non-insect Invertebrates | 5 | 0 |

| Dragonflies and Damselflies | 68 | 33 |

| Beetles | 15 | 4 |

| Butterflies and Skippers | 29 | 5 |

| Moths | 122 | 29 |

| Other Insects | 38 | 0 |

| Significant Animal Assemblages | 7 | 0 |

| 489 | 211 |

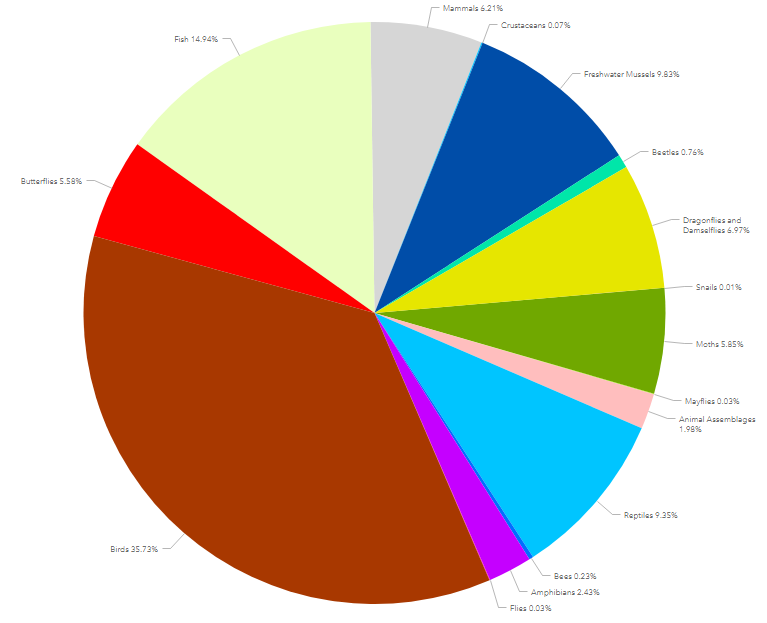

Percent of NYNHP occurrences by taxon.

As of 2020, the NY Natural Heritage Database has over 6,000 animal records. Data come from a variety of sources, such as our own field surveys, the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation, other agency and nonprofit conservation partners, and community (citizen) scientists.

Recent Changes in Our Database

White Nose Syndrome has had a devastating effect on bat populations across the country. Populations were carefully monitored for years by NYS DEC to determine to long-term effects of WNS. As a result, we are now tracking five bat species, an increase of three species.

We have also seen impressive success stories. One notable example is the result of NYS DEC efforts to restore the Bald Eagle population in New York. Bald Eagles suffered from DDT poisoning until the 1970s. But as of 2020, there are hundreds of breeding Bald Eagle pairs throughout the state, including, for the first time, breeding pairs on Long Island in recent years.

In addition, in recent years we started monitoring bumble bees (nine species) and lady beetles (three species).

Community Science

We incorporate community (also called citizen) science data from a variety of sources into our database. We accept data directly from individuals through our online rare animal reporting form. We also use data from other citizen science platforms, such as iNaturalist and eBird.

We were recently involved in a study concerning how citizen science can support regulatory review, the process where solar, wind, and other development projects are reviewed for their environmental impacts. We reviewed 27,605 eBird records for six rare species in NY: Black Tern, Harlequin Duck (non-breeding), Red-headed Woodpecker, Seaside Sparrow, Upland Sandpiper, and Yellow-breasted Chat. Using these eBird reports we were able to add 27 new known locations used by these rare species, a 19% increase over existing records. The known area occupied by Seaside Sparrows more than doubled and we were able to estimate the range extent of Yellow-breasted Chat for the first time in New York. The continual flow of data coming into citizen science platforms is very important to our program because we can obtain data at a scale not possible with only our staff scientists.

Young, B. E., N. Dodge, P. D. Hunt, M. Ormes, M. D. Schlesinger, and H. Y. Shaw. 2019. Using citizen science data to support conservation in environmental regulatory contexts. Biological Conservation 237: 57-62.

Nov. 15, 2020 | Updated Feb. 13, 2021, 10:28 a.m.